Robert Thirsk first went to space in 1996. He initially studied medicine, but when he was a resident at a hospital in New Brunswick, he saw a newspaper ad calling for applications for a new astronaut program Canada was starting. He applied immediately. Photo: Rémi Thériault

As a young boy growing up in the early 1960s in Powell River, a British Columbia city that was then famous for having the largest pulp and paper mill on the planet, Bob Thirsk says he never gave much thought to the limitless expanse of outer space far above the city’s smoke-grey skies, nor the fact that humans were beginning to journey there on space-age rockets.

But that all changed the day his Grade 3 teacher at Grief Point Elementary School brought a radio into the classroom and let her students listen to a live broadcast of American astronaut John Glenn as he circled the Earth in the first manned orbital flight in February 1962.

“It was the first time I remember hearing the word ‘space’ and learning that a career called ‘astronaut’ existed,” Thirsk recalls. “For me, it was transformative.”

A lifetime later, Thirsk looks back with gratitude on the actions of that teacher, Shirley Cole. They launched him on a trajectory to membership in one of the most exclusive clubs on Earth. As of June 2020, the former Canadian astronaut is one of only 565 people on the planet, including 10 Canadians, who have gone into space. And he’s done it twice, the second time on a six-month mission to the International Space Station in 2009, becoming the first Canadian to do a long-duration space flight.

A federal retiree since 2014, Thirsk now spends much of his time promoting space exploration and the democratization of space travel through technological innovation, higher education and the pursuit of excellence by people in all areas of human endeavour.

“We need to develop space like pioneers do in any new frontier,” says Thirsk, who joined the National Association of Federal Retirees in 2019. “We need to keep learning and investing in things like non-chemical rockets so we can bring down the cost and start flying thousands of people there every year.”

Whether on his website, in blog postings or at speaking engagements such as the 2017 TED talk he gave in Calgary titled, “How spaceflight changed my perspectives on our planet and humanity,” Thirsk is eager to share his insights on everything from the harsh realities of life in space and the challenges of space travel to the conscious-altering impacts of being in space and the drive and determination required to make it there.

“I’ve been privileged to work with innovative organizations that are not risk-averse and colleagues who inspired me to perform at the highest levels imaginable,” Thirsk says. “My goal now is to try and pass on the lessons I’ve learned in the hope they inspire others to dream big and to help them reach their goals.”

Thirsk, who lives in Ottawa, delivers a sobering yet optimistic message about the need for personal commitment and collective action to tackle the scientific conundrums facing human travel to Mars and beyond and to solve problems such as climate change that threaten life on Earth.

“I tell people to focus on their dreams, make sacrifices and get a strong educational foundation,” says Thirsk, who continues to work with the Canadian Space Agency. He served recently as chairman of an expert group on the potential health-care and biomedical roles Canada could play in the human exploration of deep space. Another piece of advice for young people? Get out of your comfort zone, “stretch yourself mentally, emotionally and even spiritually.”

The 66-year-old also co-leads a research team of International Space University alumni, whose members are investigating the effects of space flight on neuroperception, and is a board member of Vancouver’s LIFT Philanthropy Partners.

Teamwork is key to success in space. Shown here are the crew members of Space Shuttle Mission STS-78 — a 1996 mission to conduct medical and manufacturing research. Thirsk is on the lower right.

Life's Early Lessons

Thirsk, the second in a family of three children, began learning those life lessons at an early age. Both of his parents — his father, Lester, who worked for Marshall-Wells, a company that ran a chain of hardware stores, and his mother, Eva, who was a secretary — encouraged their kids to participate in sports, work hard and be involved in activities at school and in the community.

“I was always active, with little idle time,” recalls Thirsk, who took up competitive hockey, swimming, squash and wrestling, the latter a sport in which he became a provincial champion. “I did well in all school subjects, but especially the sciences and math.”

Thirsk credits his late parents for instilling in him the confidence and skills needed to succeed in life.

“Our father was a dreamer and a visionary who always encouraged us to pursue our dreams,” Thirsk says. “Our mom complemented him perfectly. She was very pragmatic and well organized.”

After moving with his family to Calgary after Grade 4, Thirsk’s interest in space piqued again in late December 1968 when he watched a broadcast of the Apollo 8 mission — the first manned spacecraft to leave Earth’s orbit and fly to the moon and back — at the Chinook Centre mall.

“It was Christmas Eve and I went there to go shopping, but ended up in the TV department of the Simpson Sears store all night,” Thirsk recalls. “I knew right That desire grew when Thirsk saw American astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walk on the moon.

“Though it was only American astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts who flew in space then, I hoped that one day Canadians would have the opportunity,” Thirsk says.

After moving again with his family to Winnipeg when he was in high school, he returned to Alberta to do an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Calgary.

He followed that up with a master’s of science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1978 and then a degree in medicine from McGill University in 1982.

“My engineering and medical education was a pathway to develop skills relevant to a space program,” Thirsk says. “Skills that could develop technical solutions to medical problems of spaceflight like cardiovascular de-conditioning and musculoskeletal atrophy.”

Turning Points

During his medical studies, Thirsk met Brenda Biasutti, a clerk in the orthopedics clinic at the Montreal General Hospital. The couple later married in the chapel of McGill University.

In early 1983, while working as a resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Dalhousie, N.B., the newly minted Dr. Thirsk saw a newspaper ad calling for applications for the new astronaut program Canada was starting after receiving an invitation from NASA to fly Canadians on upcoming Space Shuttle missions. That ad changed his life.

“The next day my application was in the mail.”

Six months later, Thirsk and five other Canadians — Marc Garneau, Roberta Bondar, Steve MacLean, Bjarni Tryggvason and Ken Money — were chosen as the Original Six of the country’s new astronaut corps. (Since 1983, Canada has only recruited 14 astronauts, nine of whom have participated in 17 space missions.)

The new astronauts’ training began in early 1984 at the then-new Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas. Thirsk was assigned as backup for Garneau, who would be the payload specialist on a shuttle mission that October. Garneau became the first Canadian to go into space.

“We did identical training; we always knew that if I got sick Bob would go,” recalls Garneau, now Canada’s transport minister. “For sure it was disappointing for him when I went up and he stayed behind. I remember him telling me it was like going to the cinema and watching a great movie that everyone is talking about, but having to leave just before the end. But what struck me most was how gracious Bob was. He’s a very modest person who always thinks about other people.”

Garneau also credits Thirsk with helping him cope with the rigorous training regime. “It was a very special link in our friendship.”

For the next 13 years, Thirsk trained, notably serving as crew commander for two space-mission simulations.

During that time, he and Biasutti moved to Houston’s astronaut-rich Clear Lake neighbourhood near the Johnson Space Center. They raised three children — Lisane, Elliot and Aidan — and were actively involved in their activities, with Thirsk helping coach high school hockey.

Nasa Photo

Three, Two, One...Blast Off!

His chance finally came in 1996 when he flew to space as a payload specialist with six other crew members on Space Shuttle Mission STS-78, a 17-day mission to conduct 43 life-science experiments.

Thirsk says he didn’t look out the window until 20 minutes after launch, when the Shuttle Columbia launched skyward with seven million pounds of thrust.

“I was too busy with my duties and supporting those of my colleagues,” he says. “But when I finally looked and saw the curvature of the Earth and the unique blue of the oceans, a chill went down my spine. I remember thinking, ‘Bob, you’ve done it, you’ve fulfilled a dream. You’re the luckiest person off the planet!’”

It would be another 13 years before Thirsk returned to space, this time launching from Kazakhstan in a Russian Soyuz spacecraft to spend six months aboard the International Space Station (ISS) with five international crewmates.

The 188-day mission involved multidisciplinary research, complex robotic operations and maintenance and repair work on the space station’s systems and payloads.

“The alien environment of space flight vacuum, extreme temperatures, weightlessness — has not impeded the ability of humans to explore and be productive,” Thirsk says. “We quickly adapt. During my own space missions, I quickly learned to fly gracefully about the spacecraft like Superman. After a few days in space, it felt as though I had been born there.”

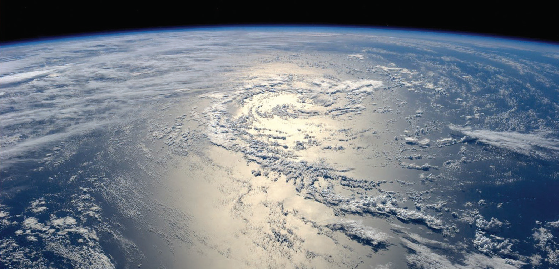

During his downtime, Thirsk says he eschewed the space station’s well-stocked library and films in favour of looking down on the blue marble-like Earth below.

“Our home planet is gloriously beautiful,” he says. “Deserts come in a hundred shades of colour. A thunderstorm is a powerful phenomenon to behold. Viewed from above, mountain ranges, erupting volcanoes and ocean reefs are mesmerizingly majestic.”

Julie Payette and Robert Thirsk aboard the ISS. Photo: NASA.

According to Thirsk, the ISS mission was the crowning touch to a 30-year career. “The skill sets an astronaut acquires are incredible,” he says. “You work with the best people and you use the best technology. You get pushed to your limits,but your performance increases becauseyou’re working with people who excel.

“Teamwork,” he added, “has been the crux of my career. If you’re going to take on audacious challenges like space flight, you need the best people with the best skills, but who also have the ability to communicate openly, to be diplomatic, to accept responsibility for mistakes and to share credit for accomplishments.”

For Belgian astronaut Frank de Winne, who spent six months with Thirsk on the ISS as its first European commander, his Canadian colleague epitomized those qualities.

The former fighter pilot who now heads the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne, Germany, says on the ISS, issues arise because you have a group of people living and working in a confined space.

“Bob was the engineer and doctor. He was also very much the typical Canadian gentleman who is very thoughtful and thinks things through. Whenever we had an issue, I would ask Bob for advice on the best way to go forward. I learned a lot from him,” de Winne says.

Staying active in retirement

After retiring from the space agency in 2012 — the same year he was awarded the Order of B.C. after being nominated by teacher Shirley Cole — Thirsk spent two years as vice-president with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in Ottawa before retiring from the federal government. He then served a four-year stint as chancellor of the University of Calgary, a role that required him to commute from Ottawa to attend fundraising activities, chair the school’s senate and attend board meetings.

In addition to doing space and education advocacy work, he travels with his wife to visit their two youngest children, who still live and work in Houston, or to see old friends such as hockey legend Bobby Orr, whose sweater and 1972 Stanley Cup ring Thirsk carried into space.

Thirsk works at staying in shape by watching what he eats, walking his son’s Australian Shepherd four times a day and working out daily for 90 minutes with an elliptical machine and barbells in his home gym.

“I’ve cut junk food from my diet and eat less red meat,” Thirsk says. “I work out in the late afternoon. It’s the last thing I do in my day.”

Remaining active, he added, is key to staying healthy and enjoying retirement to its fullest.

“Burn off more calories than you ingest,” he advises. “However, don’t focus solely on aerobic conditioning. Muscles require strength training and will atrophy without regular loading. Play recreational sports in order to maintain athleticism, balance and power.”

To cope with long-term isolation during the pandemic, Thirsk says people need to approach it like a space mission. “It will be a marathon, not a sprint,” he says. “Ensure you have reserves to draw upon in later weeks. Attend to your sleep, diet and exercise (and) restrict your workload to reasonable limits.”

Living together in close quarters, even with loved ones, can be a challenge.

“Be aware of your personal quirks [and] modify your behaviour to accommodate others’ needs and make the living environment pleasant for all.”

He also encourages pitching in. “Every member of a crew contributes to the quality of group living,” he says. “Do your share of the unglamorous household tasks.”

Though the pandemic has upset people’s daily routines, Thirsk says they should keep things as normal as possible. “Retain structure, focus and purpose, create a to-do list in the morning and work through it each day.

“Consider this period of self-isolation an opportunity. Catch up on your backlog of reading, writing and phone calls with friends. Undertake something you’ve never done before. Write thank-you cards to frontline workers to show your appreciation.”

He advises thinking of self-isolation as astronaut training.

NASA photo