Retirees and employees alike continue to have to chase money they’re owed with minimal communication from the government side.

In engineering, redundancy means duplicating key systems in case one of them fails or is corrupted. You have a problem, you go to the backup. Unfortunately, in the case of the Phoenix pay system, to save money and time, there was no redundant system in place when it was switched on, and Canadians are still paying for that mistake six years later.

Sage magazine decided to update our readers on the Phoenix issue because Federal Retirees is still getting weekly requests to help members whose retirement packages have been hindered by the boondoggle.

Some cases are fairly mild. Take Joan Kinnie’s situation. She retired in December 2010 after 37 years with the federal government — the last 20 with Health Canada. For the next three years, she accepted some casual work with the justice department, most recently in 2013. It was during this casual work period that she suspected she was affected by Phoenix pay mistakes.

In 2020, an agreement was negotiated between the Treasury Board of Canada and the Public Service Alliance of Canada to pay up to $2,500 per person to those harmed by the Phoenix pay system between 2016 and 2020 and by the late implementation of the 2014 collective agreements.

Kinnie, who has been a member of Federal Retirees since 2011, applied for that compensation in 2020. She never received acknowledgment of her application. Later that year, $314 mysteriously appeared in her bank account. Then, soon after, $279 appeared. A friend had had money clawed back, so Kinnie was wary and tried to find out what was going on, to no avail. If you're retired, you can’t access the employee system to check your own file, so the task is near impossible on your own.

“If they communicated at all,” she says, “maybe this would be an easier process.”

The kicker is that early this year she received two T4 slips from Justice Canada, meaning she owes some taxes and is in the dark as to why, since she can't get anyone on the phone to answer her questions.

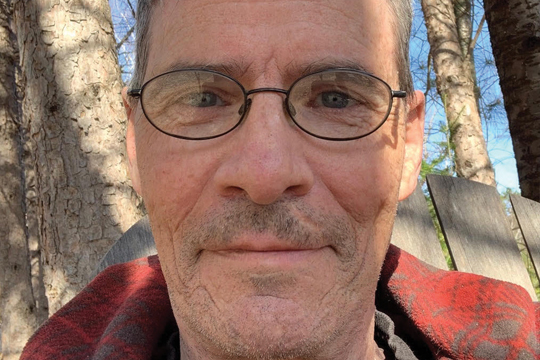

Other cases, such as Richard Cloutier's, are more serious. He spent 30 years working for the Department of National Defence and then five more years with the Immigration and Refugee Board, retiring in 2016 near Maniwaki, Que. He was owed roughly $52,000 in severance for his years of service and had directed those funds to be invested in his RRSP. In January 2017, approximately $28,000 was deposited into his account, with no accompanying documents. Two months later another $20,000 appeared in his account, again with no communication. By Cloutier's calculation, he thought he was still owed $3,438.24 for his severance. Having heard the tales of clawbacks, and seeing the amounts he’d received were incorrect by his calculations, he sat on the funds and didn't move them into his RRSP himself, just in case the government came for the money.

He contacted the Treasury Board in 2017 and a ticket for his file was created, but not much else happened for a while. Eventually he would be told that there had been a “transition payment adjustment” on his paycheque for the first payment that accounted for his missing $3,438.24 in severance. Having never received any notice for either payment, this at least answered one question. He was informed he could apply for interest on the late severance from the date he retired to the date he received funds, as well as compensation for how it affected his 2017 taxes, since that’s when he received the money.

Richard Cloutier figures he’s still owed $21,026.07 by the federal government after a series of payments that came without explanation.

Then the CRA informed him he owed an extra $18,283.52 for his 2016 taxes. The CRA was counting the severance as income. He paid his tax bill.

Cloutier figures that since then he’s lost another $2,742.55 in investment returns he would have gained had the funds been correctly deposited into his RRSP, assuming the investment made a modest three per cent return for those five years.

In total, that adds up to $21,026.07 he says he’s owed. He’s now on his second case ticket with nothing resolved.

“I’ve been waiting for six years for something to happen,” Cloutier says. “How long am I supposed to wait?”

Running the finances of government is, of course, not easy. The federal government is Canada’s single largest employer: There are nearly 380,000 public servants and within that, there are more than 100 organizations with payrolls.

But things were working like a Swiss watch until the Harper government’s Deficit Reduction Action Plan in 2009 decided to look for $70 million in annual savings by consolidating the 40-year-old Regional Pay System (RPS) into a single payment centre. Phoenix rose in Miramichi, N.B., from the ashes of the RPS. About 2,700 folks who worked in payroll were let go, and with them went their institutional knowledge.

As problems appeared and employees weren’t getting paid, or were overpaid and then not paid because of clawbacks, some people lost their houses and went bankrupt through no fault of their own.

When the Trudeau government took over in late 2015, it was saddled with a floundering Phoenix, one with no redundancies built in. It had no choice but to try and fix this broken bicycle while riding it downhill.

According to the Public Service Pay Centre dashboard, as of Feb. 16, 2022, there were 139,000 financial transactions beyond normal workflow. On a positive note, that’s down from almost 384,000 at the beginning of 2018.

The current estimated price tag to finally fix Phoenix will be $2.3 billion by 2023.

Donna Lackie is a special projects officer who works on Phoenix for the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). She lives and works in Ottawa and has been working this file for 12 years now. She says in terms of retirees, the one consistent complaint she hears about is the “abysmal communication.”

Lackie says she’s heard many stories like Cloutier’s of incomplete payments and payments not put into RRSPs and then declared income. She thinks it’s simple human error in the case of funds not being deposited into RRSPs. And the system has trouble fixing its own mistakes. She says the pay centre now employs many, many qualified and competent compensation advisers. But the backlog is enormous and people can only get so much done in a 7.5-hour work day.

As 2022 dawned, Canadians were told there are 21,000 federal employees who have overpayments from 2016, the year Phoenix began trying to flap its wings. And in March 2022, when IBM’s original Phoenix system contract was set to expire, the government extended it for one year, to the tune of $106 million, taking the total for the faltering system to $650 million so far.

That’s a lot of people getting letters telling them they owe a lot of money from six years ago. If current employees don't respond in four weeks, the government says it will garnishee wages, despite PSAC’s outrage at these tactics.

By law, the government only has six years to pursue overpayments, after which they must be written off as debt.

“So every month they send out another group of letters to protect the time limit,” Lackie says. She adds that there are also currently 35,000 people waiting to have their pay file termination cases resolved.

According to officials with Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), as of March 2022, there are 1,187 identified severance cases still to be processed at the pay centre. While employees say they’ve made significant progress reducing the backlog, last year brought an increase in new transactions, slowing progress in resolving outstanding cases.

Greg Luchinski has one of those outstanding cases and he’s feeling frustrated and disheartened. After 35 years with Environment Canada, he retired in 2016 in Winnipeg. It took him nearly four years and the help of his local MP to finally receive his severance package. But he’s still owed interest and compensation for having to wait so long for that payout. Yet, after three long years of trying, he’s ready to give up on it almost.

“An apology might be better,” Luchinski says, adding that he really just wants to see the system improved.

But maybe things are improving — if only slightly and very slowly.

Federal Retirees member Jean-Marc Daigle, who lives in Chelsea, Que., with his wife, Line, retired in 2019. Early in 2022, and after much cajoling of PSPC, he happily received his severance. He’d like the $1,000 he’s still owed for a leave credit, but he, too, doesn’t hold out much hope he’ll ever get it.