The indexation rate for public service pension plan benefits comes at the end of each year, but how is it calculated, and how does it respond to inflation?

On Nov. 1, 2021, the Treasury Board Secretariat announced that the annual indexation for the federal public sector pensions would be 2.4 per cent.

Some plan members are shocked. After all, haven't the media been reporting historically high levels of inflation throughout the month of September?

Several members wrote to us and said that indexation did not reflect inflation and the true increase in cost of living. Others compared our members’ indexation to different pension plans, like Social Security in the United States.

- What is indexation?

- How does indexation differ from inflation?

- What is the difference between the Consumer Price Index and cost-of-living?

- What does all this mean for my pension?

- What about other pension plans?

What is indexation?

Indexation is an annual increase to the pensions of federal public servants and veterans. Generally, Consumer Price Index (CPI) data is used to calculate annual indexation to pensions. How pension plans use the data and derive their indexing rate can vary.

In the case of federal retirees’ pensions, the annual CPI-based indexation applied each January is based on the percentage increase in the monthly average CPI over the preceding two years. The calculation uses data over the 12-month period from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30. The last three months of the year are incorporated into the next year’s rates.

The CPI is a measure of changes in the price of Canadian consumer needs. Statistics Canada measures the price of a fixed list or basket of goods and services that most Canadians purchase. These include food, shelter, household operations, furnishings, clothing, transportation, personal care, recreation, education, alcohol and now even recreational cannabis. The basket of goods is based on data from the Survey of Household Spending, and each item in the basket represents consumer spending patterns and is given a proportionate weight. The weights reflect the relative importance of each good or service, based on each item’s share of total household consumption.

CPI doesn’t necessarily reflect the increases of what you as an individual spend your money on — you may not care that booking a hotel or buying clothing and shoes is less expensive than it was a year ago, but those prices are also included.

How does indexation differ from inflation?

Inflation and indexing are not the same. Inflation is a measure of the increase of price of goods and services in general terms. Commonly, we use CPI to calculate inflation, though there are other measures like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflator, cost-of-living indices, commodity price indices and so on.

Indexation, on the other hand, is a technique that is intended to counteract the long-term effects of inflation in the interest of maintaining purchasing power, and it also uses the CPI as part of its calculations. Over time, indexation keeps pace with inflation.

What is the difference between CPI and cost-of-living?

Cost-of-living indices are conceptual measurements of the amount consumers need to spend, in a certain place and time, to maintain a standard of living or a given level of “well-being.”

The CPI and pension indexing approximate the cost of living — but pension indexing doesn’t necessarily reflect the cost increases that can make it difficult to maintain a standard of living in a given place.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) data compares, over time, the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services — from food and shelter to alcoholic beverages and even recreational cannabis.

What does all this mean for my pension?

Because both indexation and inflation are based on CPI — they tend to follow in lockstep. Sometimes one will be higher than the other, but they eventually catch up to each other.

To illustrate this pattern, let’s examine two graphs.

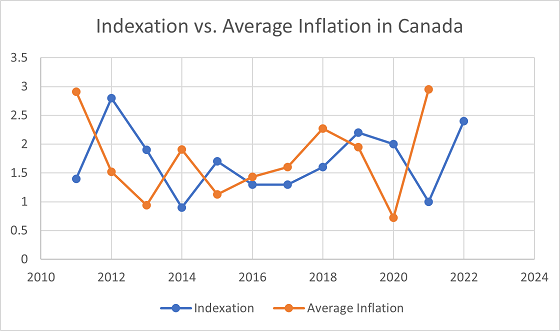

The first graph shows the rise and drop of inflation and indexation over the last 10 years.

Graph 1: Inflation and indexation since 2010.

In some years, indexation is higher, while in others, inflation is higher, but they are both very similar and catch up to each other over time. If inflation is high in one year, indexation tends to reflect that in the following year. Over the span of this graph, the difference between both was 0.05 per cent.

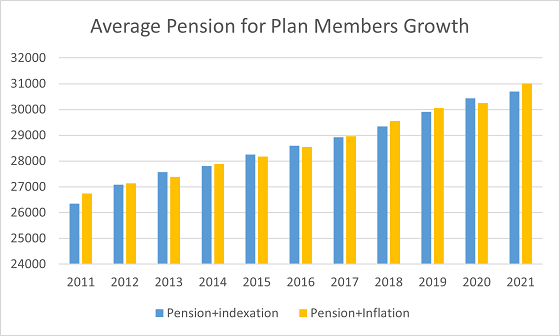

The second graph takes the average pension for plan members in 2011 ($25,591) and compares how the pension would have grown with indexation versus how it would have grown with average inflation in Canada.

Graph 2: How the average pension would have grown with indexation compared to how it would have grown with average inflation.

Much like the previous graph, we can see how inflation and indexation keep up with one another over the years, leapfrogging one another in some years, but always trending similarly.

Because federal retirees’ pension indexation accumulates or compounds year over year, a pension worth $25,591 in 2011 would be worth almost $30,000 in 2021. (It is important to note that the average pension increases at a different rate as it also reflects demographic changes, salary changes and the rates at which individuals retire.)

But what about “X” plan?

Some pension plans and other pension entitlements (such as Social Security in the United States) calculate their indexation differently. The differences you see in indexation rates in other plans can be a result of the time period they weigh in their calculations (for instance, the New Brunswick Teachers’ Pension Plan announced an increase of 1.46 per cent for 2022 as their plan is based on the period of June to July of the previous year) or location (the United States had a much higher level of inflation compared to Canada throughout 2021). Not every plan uses the same formula — some have a cap for increases, and some have a minimum increase. Some plans have no indexation at all or partial indexation for retirees. It entirely depends on that plan’s formula.

When looking at different pension plans, it can be tempting to focus on what makes another’s grass greener, but every plan’s formula is different — and calculations are often more complicated than you might think.

When prices at the pumps keep going up and you have to make your dollar stretch at the grocery till, it may feel like federal public sector pension plans in Canada are getting cheated. However, indexation is being applied correctly over time, and pensioners who have built-in pension indexation are able to preserve their spending power, compared to plans that approach indexation far more conservatively — or not at all.